It’s a simple question – is it cheaper to own an electric vehicle (EV) or a gas-powered car? It doesn’t have a simple answer.

A new study from the University of Michigan finds that EV ownership costs can vary widely based on where you live and how you use your car.

The same has long been true of gas-powered vehicles. Taxes, fees, and parking costs make car ownership prohibitively expensive in Manhattan and trivial for many in Wisconsin. As of this morning, gas costs $5.11 in Trinity County, California, and $2.37 in Wilbarger County, Texas. Your math isn’t everyone’s math.

But EVs are new, and the math behind owning one is complex.

Researchers found that ownership costs for a “300-mile range midsize electric SUV” could vary by almost 40% between locations.

Related: How Much Does It Cost to Charge an EV?

The research was funded by the Responsible Battery Coalition, a group of companies and academic organizations focused on researching and developing more advanced batteries and ways to recycle batteries efficiently.

A Home Charger Makes the Biggest Difference

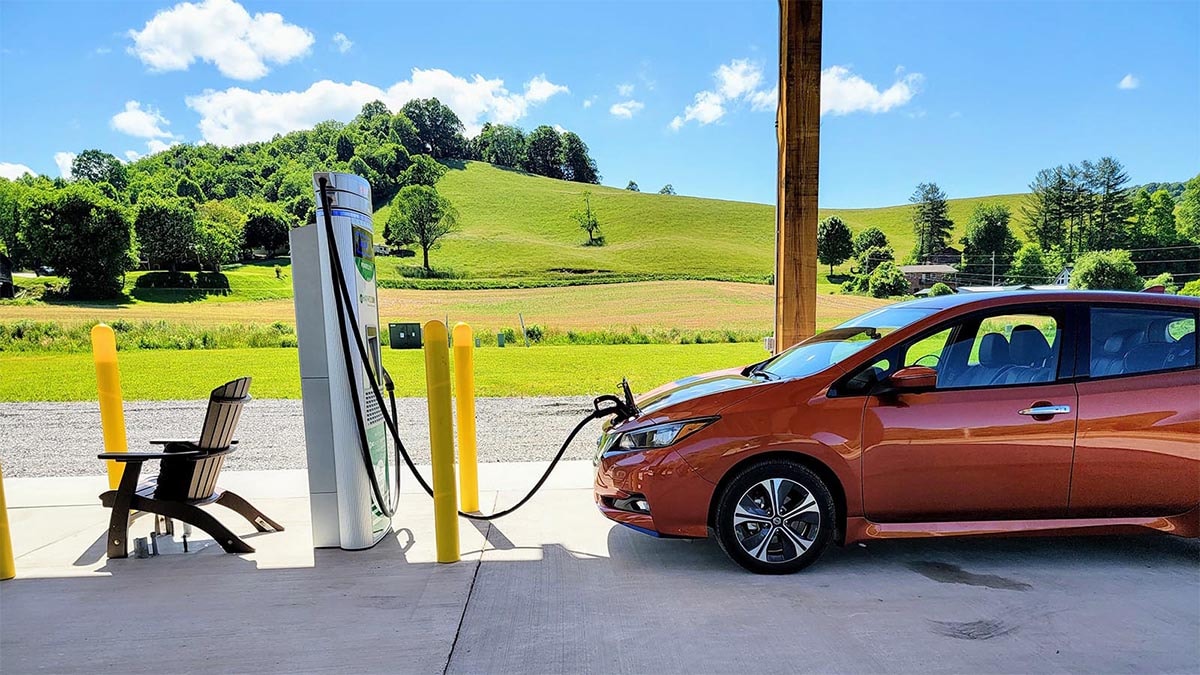

The single most important factor in whether an EV is affordable is whether you have access to a home charger, researchers found. Relying on public charging stations is more expensive. “Home charging access reduces the lifetime cost by approximately $10,000 on average, and up to $26,000.”

The researchers developed the most complex cost-of-ownership model we’ve seen, taking into account everything from gasoline and electricity prices in various cities to state incentive programs and even temperature patterns and their effect on batteries.

Related: Hidden Costs of Owning an Electric Car

The results resist easy conclusions. But the researchers found a few.

Break-Even Point Can Span Years

The most expensive place to own a car “across all classes and powertrains is New York City, while the least expensive city depends on class and powertrain.” Cleveland is the least expensive place to own an EV. It’s also at the bottom of the list for gas-powered cars, though gas-powered trucks are cheapest in Houston. Boston and Washington, D.C., are the least expensive places to drive a hybrid.

The researchers attempted to project when owners would break even – saving enough money on operating costs to offset the higher purchase cost of an EV. Those figures vary widely based on size, too. “Smaller vehicles and shorter-range vehicles break even more quickly, with 200-mile range compact and midsize sedans breaking even in 3−7 years,” the researchers said.

Compact and midsize sedans with a range of around 300 miles break even in nine to 20 years. The largest vehicles — SUVs and pickups with ranges over 300 miles – found a break-even point in some cities but not others. “For all 400-mile range” EVs, the researchers write, “the break-even time exceeds 25 years.”

Smaller EVs Less Expensive Than Gas Vehicles; Larger EVs Not

“In general, we find that small and low-range EVs are less expensive than gasoline vehicles,” they wrote.

Larger, long-range EVs, on the other hand, “are currently more expensive than their gasoline counterparts. And midsize EVs can reach cost parity in some cities if incentives are applied.”

We don’t want to force broad conclusions on a nuanced study. But there is some wisdom in the one obvious trend there – smaller EVs like the Chevy Bolt are often better financial propositions than hulking ones like the Tesla Cybertruck or Ford F-150 Lightning.

Related: Study — EVs Cost More To Repair, Less To Maintain

A buyer looking for a subcompact hatchback isn’t comparing it to full-size trucks. The math behind owning one or the other is so wildly different that they aren’t comparable decisions. That’s true regardless of what powers them.

EVs, today, make sense in some contexts. The infrastructure in some larger cities or more densely-populated areas supports them. They work well for people who own their own homes and need a car for commutes and errands. They’re not great in extreme weather, making them more practical in some parts of the country than others.

But they aren’t the right solution in other places and for more intense uses. The technology behind them will continue to develop, and the math may differ with future cars. For now, they’re right for some of us, but not all of us.